Polly Frost's Interview with Silvia Sanza

POLLY FROST: I'm a huge fan of Silvia Sanza's book "Alex Wants to Call It Love." It's funny, smart, perceptive, entertaining, daring -- just like Silvia. (Her book "Twice Real" is available here.)

I met Silvia a couple of years ago at a poetry reading. I immediately liked her and have been struck since at how generous she is towards other writers. It's all too unusual to meet artists or writers who are, God knows!

But Silvia is that rarity: a genuine bohemian, someone who was born to live the arts life, not someone who aspires to it, or who wants to use it just for a career. So it was a pleasure to read "Alex Wants to Call It Love" and love it.

Well, how could I not love a book that's deliciously raunchy and beautifully written? Here's a passage from "Alex Wants to Call It Love":

“Sex is important only when it's great. otherwise, it's an inconvenience. If it doesn't make you high as a mountain, why bother? if it's too tentative, who needs it? And with Alex sex had become something to do, like eating junk food. It passed the time, wiped up the excess passion, and hid the twisting and groaning emotions, it was as easy as shaking hands and that made it too easy. She was after untamed pounding.”

Seeing potential in her acting as well as her writing, I roped Silvia into performing in "The Fold," the movie I produced and co-wrote with my husband, Ray Sawhill, and the director Matt Lambert. We all loved her acting and what a good sport she was on a long day of shooting in February. (See Silvia in the trailer from “The Fold” at http://thefold.tv.)

INTERVIEW

POLLY: As a fan of your book Alex Wants to Call It Love, I'd like to ask if your new book is similar in tone?

SILVIA: Tone. I have to think about that word for a minute. Tone can mean quality, attitude, atmosphere, ambiance, mood. My new book is much the same in that it is contemporary New York characters but my characters, like me, are older -- their needs are singular, their experience speckled. Still struggling but with valiant strides.

POLLY: What's your writing process?

SILVIA: I am always writing bits and pieces. I sit on stoops, in parks, on curbs and listen to the sounds of the city. I sketch words. Scraps of paper are tossed into file folders and plucked out for inspiration. Characters often write themselves. The shirred yellow empire dress I see in a Soho window becomes the dress that catches the eye of a man walking down Prince Street looking for a lover. I write a first draft longhand on yellow legal pads with #2 pencils; a second draft goes on the computer. I like to write sitting down on the rug in my tiny living room. If I get distracted for too long a time by my own four walls, I escape to the Jefferson Market Library and sit at one of the round tables upstairs where I can defer the temptation to check my e-mail twenty times a day.

POLLY: How much does your own experience/circle of friends enter into your work?

SILVIA: Very much except I inject it all with a exceedingly healthy dose of fiction. I save everything: letters, postcards, notes, diaries from when I was 12 years old, shopping lists people leave in their baskets at D’Agostino’s. At family thanksgiving dinners I listen hard so I can write about the whole thing when I get home. I listen for the things that remain unsaid. I listen for what’s going on beneath the surface. I’ve always done that. Then I mix the characters up: one from Column A, one from Column B, two from Column C. A man from one of those family dinners gets matched with a woman (or man) from a completely different social occasion. Characters meld and blend and set and bond in that marvelous world of fiction. I let them tell me what comes next.

POLLY: What role does eroticism/sex play in your writing?

SILVIA: It would be impossible not to have sex in my writing. Sex is an emotion, painfully addictive, powerfully soothing, wildly absurd, blessedly hilarious and validly and vividly alive in everyone, even those who choose to deny it. I myself am driven by a bundle of sexual tension but sometimes pull back for my own safety. I use that part of me in my writing, too -- that calculated disentanglement allows me to create a new dimension of character . . . a new way to measure.

POLLY: What's the title of your new book?

SILVIA: My new novel is called Negative Space. It is an analogy between the bleak aftermath of 9/11 and the death of my husband who I adored. He was an environmental sculptor and often talked about “negative space”. I was bulldozed by the harsh loneliness of negative space after his death, then came the sweeping far-reaching negative space of 9/11 and the collapse of the twin towers, and then a nose-dive into the negative space of the internet in a grisly chase for love. Let’s say it starts out based on a true story and goes from there.

I met Silvia a couple of years ago at a poetry reading. I immediately liked her and have been struck since at how generous she is towards other writers. It's all too unusual to meet artists or writers who are, God knows!

But Silvia is that rarity: a genuine bohemian, someone who was born to live the arts life, not someone who aspires to it, or who wants to use it just for a career. So it was a pleasure to read "Alex Wants to Call It Love" and love it.

Well, how could I not love a book that's deliciously raunchy and beautifully written? Here's a passage from "Alex Wants to Call It Love":

“Sex is important only when it's great. otherwise, it's an inconvenience. If it doesn't make you high as a mountain, why bother? if it's too tentative, who needs it? And with Alex sex had become something to do, like eating junk food. It passed the time, wiped up the excess passion, and hid the twisting and groaning emotions, it was as easy as shaking hands and that made it too easy. She was after untamed pounding.”

Seeing potential in her acting as well as her writing, I roped Silvia into performing in "The Fold," the movie I produced and co-wrote with my husband, Ray Sawhill, and the director Matt Lambert. We all loved her acting and what a good sport she was on a long day of shooting in February. (See Silvia in the trailer from “The Fold” at http://thefold.tv.)

INTERVIEW

POLLY: As a fan of your book Alex Wants to Call It Love, I'd like to ask if your new book is similar in tone?

SILVIA: Tone. I have to think about that word for a minute. Tone can mean quality, attitude, atmosphere, ambiance, mood. My new book is much the same in that it is contemporary New York characters but my characters, like me, are older -- their needs are singular, their experience speckled. Still struggling but with valiant strides.

POLLY: What's your writing process?

SILVIA: I am always writing bits and pieces. I sit on stoops, in parks, on curbs and listen to the sounds of the city. I sketch words. Scraps of paper are tossed into file folders and plucked out for inspiration. Characters often write themselves. The shirred yellow empire dress I see in a Soho window becomes the dress that catches the eye of a man walking down Prince Street looking for a lover. I write a first draft longhand on yellow legal pads with #2 pencils; a second draft goes on the computer. I like to write sitting down on the rug in my tiny living room. If I get distracted for too long a time by my own four walls, I escape to the Jefferson Market Library and sit at one of the round tables upstairs where I can defer the temptation to check my e-mail twenty times a day.

POLLY: How much does your own experience/circle of friends enter into your work?

SILVIA: Very much except I inject it all with a exceedingly healthy dose of fiction. I save everything: letters, postcards, notes, diaries from when I was 12 years old, shopping lists people leave in their baskets at D’Agostino’s. At family thanksgiving dinners I listen hard so I can write about the whole thing when I get home. I listen for the things that remain unsaid. I listen for what’s going on beneath the surface. I’ve always done that. Then I mix the characters up: one from Column A, one from Column B, two from Column C. A man from one of those family dinners gets matched with a woman (or man) from a completely different social occasion. Characters meld and blend and set and bond in that marvelous world of fiction. I let them tell me what comes next.

POLLY: What role does eroticism/sex play in your writing?

SILVIA: It would be impossible not to have sex in my writing. Sex is an emotion, painfully addictive, powerfully soothing, wildly absurd, blessedly hilarious and validly and vividly alive in everyone, even those who choose to deny it. I myself am driven by a bundle of sexual tension but sometimes pull back for my own safety. I use that part of me in my writing, too -- that calculated disentanglement allows me to create a new dimension of character . . . a new way to measure.

POLLY: What's the title of your new book?

SILVIA: My new novel is called Negative Space. It is an analogy between the bleak aftermath of 9/11 and the death of my husband who I adored. He was an environmental sculptor and often talked about “negative space”. I was bulldozed by the harsh loneliness of negative space after his death, then came the sweeping far-reaching negative space of 9/11 and the collapse of the twin towers, and then a nose-dive into the negative space of the internet in a grisly chase for love. Let’s say it starts out based on a true story and goes from there.

Silvia's Interview

with Suzannah Troy, Activist

November 9, 2011

The first thing you notice about Suzannah Troy is that she is never without a smile. But in her heart there is a roar, the rumble of someone who demands justice. She talks in capital letters and she talks a mile a minute. I hang on to every word. She scares me with her brilliance and nonstop energy. I have watched and listened to her often during our tireless struggle for a new hospital at the site of St. Vincent’s which closed on April 30, 2010.

Where do you want to be in five years, I ask her? “In a hippie commune,” she giggles, “out in the country.”

I have a hard time picturing Suzannah out in the country. Her grandfather was born on Ludlow Street on the lower east side. Her parents lived in New York City and, in Suzannah’s words, moved “across the border” to New Jersey for her birth. When she was six weeks old her father was awarded a Fulbright in Economics and they moved to England for a year at the end of which they returned to New Jersey. When she was 11 her father was awarded a second Fulbright and the family returned to England for one more year. From the age of 21 to the present she has lived in New York City. Even with those short time-outs in other places, to me she is All New York. She is the beat of New York, the conscience of New York, the patron saint of all that is wrong with New York, and the lover of all that is wonderfully right about New York.

She was born July 15th, a cancer, ruled by the moon. Her dad is 87, a retired economics professor and WW2 veteran, to whom Suzannah is devoted. She is a licensed massage therapist and after 9/11 she did massage on rescue workers, the military, and members of the FDNY and NYPD who spent long days on their feet. She makes some money from Google Ad Sense via her blogs and YouTubes. Suzannah laughs and says “Google pays me and has also censored me.“ A month and a half before Mike Bloomberg’s third term, her YouTube channel of approximately 340 videos was removed for 28 hours. Google later apologized and said it was a technical glitch but Suzannah feels it was done on purpose because Bloomberg’s people knew it was a close election and wanted to silence voices in opposition. Her supporters loudly demanded the return of her YouTube channel. The audience always seems to win because Suzannah is never “off the air” very long.

What kind of art do you do, I ask? “Everything . . . everything is my art. My goal is to make you think and feel. That is my job as an artist.” She paints with words. She coins fabulous phrases like “subzero trickle down” and hails Christine Quinn “Mike Bloomberg’s ‘mini me’”. She calls herself an emotional pyromaniac who burns every bridge. Her blog and YouTube videos are notorious and she has a vast and dedicated following. She’s one of those people who “everybody knows her name.” Her iphone is an essential part of her art. Her focus is corruption. She has many causes, but her fundamental fury is that the people of New York City come last and greed comes first. In her own words, “Our leaders have high priced public relation machines but they are destroying our neighborhoods with greed and stupidity including corrupt real estate deals to mortgage meltdown and Wall Street implosion — common thread greed and stupidity have really hurt this country.”

She paints tough words but she also paints with paint, real paint. Most famous is “Mayor Bloomberg, King of New York, Is Democracy For Sale?”, the portrait she did of Mayor Bloomberg for whom she regretfully admits voting for his first two terms. On election night 2009 she was working on the painting to finish it in concert with the election results and made a YouTube documenting the event. The portrait started out lush and sensual, the paint thick, icing on a cake. She was delighted to watch the media being forced to go “off script” and have to report the truth, finally, that Bloomberg might not win. At that point of course it was too close to call. As the final results trickled in, Suzannah’s painting went the Dorian Grey route — the canvas took on his sins so to speak and the painting answers the question the political poster asks: Democracy is for Sale. Here’s a link to her blog devoted to voting for no third term for Mike Bloomberg. It features the YouTube video about the painting. http://mayorbloombergkingofnewyork.blogspot.com/2011/09/suzannah-b-troys-bloomberg-no-third.html

She gave the painting to Clayton Patterson, an artist and activist, who gave it a permanent home at his Outlaw Art Museum at 161 Essex Street.

Suzannah’s next project is Christine Quinn’s portrait and political poster with the themeVote for Christine Quinn if you want Mike Bloomberg for a fourth term.

I ask what cause is dearest to her heart and she thinks hard, calls herself an emotional nudist, and says that above all she wants a hospital at the former site of St. Vincent’s. After that, she wants hospitals in Staten Island and Queens, places doomed with losing facilities. She curses what she calls “mega dorms” in New York’s east village: NYU, New York Law, School of Visual Arts, Cooper Union, and The New School all have dorms there, an environment that caters to kids – banks, Starbucks, Duane Reade, which Suzannah feels actually hurt the community. No more, please, she says – give us hospitals. A recurring theme on her blog is that Bloomberg has the largest white collar crimes ever in New York City government history.

How did her fiery activism begin, I asked her; what fueled this intensity? It began during Bloomberg’s second term, likening her awakening to coming alive after a coma. In 2005 New York University announced their plans for a 26 story dormitory building on the site of St. Ann’s Church at120 East 12th Street. In 2006 plans were filed and construction began. Only the front façade from 1847 was preserved. Suzannah says that façade is like an albatross around NYU’s neck. She proceeded to take on NYU and the United States Postal Service who owned and illegally sold the air rights over St. Ann’s to NYU. To sell these rights legally, they had to contact the State of New York which they never did. Suzannah says that thanks to iphone she can document her activism and the nuisance and harassment that can come with the territory of being an activist. Her iphone makes her feel safe. It is an amazing tool. She also has lots of legal justice on her side. Suzannah has the greatest admiration for Norman Siegel, the famed civil rights attorney that helped her get her YouTube channel returned to her.

She sits in my dining room, iphone always in her hands, staying ahead of the game. She squirts words like “motherfucker” as she scans the news. Her sources are many and she often passes along information to journalists with investigative reporting backgrounds. She works on the side of morality and has her own beefy set of principles. People say she should be given an award for being a citizen journalist.

She admits she’s not having much fun lately, taking life too seriously. She spent this morning in front of the Rudin sales office for the luxury condos, shouting for passers-by to pay attention to the still raging fight for a new hospital, telling anyone who will listen that Rudin has ignored the community’s need for a full service hospital, paid pennies on the dollar for this prime real estate, and now stands to sell luxury condos which will have a fair market value of more than a billion dollars.

She has big plans, she tells me, for the “second part of her life” that have to do with healing. But she’s keeping them secret for now.

Suzannah’s blog can be found at http://suzannahbtroy.blogspot.com/2011/11/howard-rubenstein-rudins-pr-dont-have.html

Where do you want to be in five years, I ask her? “In a hippie commune,” she giggles, “out in the country.”

I have a hard time picturing Suzannah out in the country. Her grandfather was born on Ludlow Street on the lower east side. Her parents lived in New York City and, in Suzannah’s words, moved “across the border” to New Jersey for her birth. When she was six weeks old her father was awarded a Fulbright in Economics and they moved to England for a year at the end of which they returned to New Jersey. When she was 11 her father was awarded a second Fulbright and the family returned to England for one more year. From the age of 21 to the present she has lived in New York City. Even with those short time-outs in other places, to me she is All New York. She is the beat of New York, the conscience of New York, the patron saint of all that is wrong with New York, and the lover of all that is wonderfully right about New York.

She was born July 15th, a cancer, ruled by the moon. Her dad is 87, a retired economics professor and WW2 veteran, to whom Suzannah is devoted. She is a licensed massage therapist and after 9/11 she did massage on rescue workers, the military, and members of the FDNY and NYPD who spent long days on their feet. She makes some money from Google Ad Sense via her blogs and YouTubes. Suzannah laughs and says “Google pays me and has also censored me.“ A month and a half before Mike Bloomberg’s third term, her YouTube channel of approximately 340 videos was removed for 28 hours. Google later apologized and said it was a technical glitch but Suzannah feels it was done on purpose because Bloomberg’s people knew it was a close election and wanted to silence voices in opposition. Her supporters loudly demanded the return of her YouTube channel. The audience always seems to win because Suzannah is never “off the air” very long.

What kind of art do you do, I ask? “Everything . . . everything is my art. My goal is to make you think and feel. That is my job as an artist.” She paints with words. She coins fabulous phrases like “subzero trickle down” and hails Christine Quinn “Mike Bloomberg’s ‘mini me’”. She calls herself an emotional pyromaniac who burns every bridge. Her blog and YouTube videos are notorious and she has a vast and dedicated following. She’s one of those people who “everybody knows her name.” Her iphone is an essential part of her art. Her focus is corruption. She has many causes, but her fundamental fury is that the people of New York City come last and greed comes first. In her own words, “Our leaders have high priced public relation machines but they are destroying our neighborhoods with greed and stupidity including corrupt real estate deals to mortgage meltdown and Wall Street implosion — common thread greed and stupidity have really hurt this country.”

She paints tough words but she also paints with paint, real paint. Most famous is “Mayor Bloomberg, King of New York, Is Democracy For Sale?”, the portrait she did of Mayor Bloomberg for whom she regretfully admits voting for his first two terms. On election night 2009 she was working on the painting to finish it in concert with the election results and made a YouTube documenting the event. The portrait started out lush and sensual, the paint thick, icing on a cake. She was delighted to watch the media being forced to go “off script” and have to report the truth, finally, that Bloomberg might not win. At that point of course it was too close to call. As the final results trickled in, Suzannah’s painting went the Dorian Grey route — the canvas took on his sins so to speak and the painting answers the question the political poster asks: Democracy is for Sale. Here’s a link to her blog devoted to voting for no third term for Mike Bloomberg. It features the YouTube video about the painting. http://mayorbloombergkingofnewyork.blogspot.com/2011/09/suzannah-b-troys-bloomberg-no-third.html

She gave the painting to Clayton Patterson, an artist and activist, who gave it a permanent home at his Outlaw Art Museum at 161 Essex Street.

Suzannah’s next project is Christine Quinn’s portrait and political poster with the themeVote for Christine Quinn if you want Mike Bloomberg for a fourth term.

I ask what cause is dearest to her heart and she thinks hard, calls herself an emotional nudist, and says that above all she wants a hospital at the former site of St. Vincent’s. After that, she wants hospitals in Staten Island and Queens, places doomed with losing facilities. She curses what she calls “mega dorms” in New York’s east village: NYU, New York Law, School of Visual Arts, Cooper Union, and The New School all have dorms there, an environment that caters to kids – banks, Starbucks, Duane Reade, which Suzannah feels actually hurt the community. No more, please, she says – give us hospitals. A recurring theme on her blog is that Bloomberg has the largest white collar crimes ever in New York City government history.

How did her fiery activism begin, I asked her; what fueled this intensity? It began during Bloomberg’s second term, likening her awakening to coming alive after a coma. In 2005 New York University announced their plans for a 26 story dormitory building on the site of St. Ann’s Church at120 East 12th Street. In 2006 plans were filed and construction began. Only the front façade from 1847 was preserved. Suzannah says that façade is like an albatross around NYU’s neck. She proceeded to take on NYU and the United States Postal Service who owned and illegally sold the air rights over St. Ann’s to NYU. To sell these rights legally, they had to contact the State of New York which they never did. Suzannah says that thanks to iphone she can document her activism and the nuisance and harassment that can come with the territory of being an activist. Her iphone makes her feel safe. It is an amazing tool. She also has lots of legal justice on her side. Suzannah has the greatest admiration for Norman Siegel, the famed civil rights attorney that helped her get her YouTube channel returned to her.

She sits in my dining room, iphone always in her hands, staying ahead of the game. She squirts words like “motherfucker” as she scans the news. Her sources are many and she often passes along information to journalists with investigative reporting backgrounds. She works on the side of morality and has her own beefy set of principles. People say she should be given an award for being a citizen journalist.

She admits she’s not having much fun lately, taking life too seriously. She spent this morning in front of the Rudin sales office for the luxury condos, shouting for passers-by to pay attention to the still raging fight for a new hospital, telling anyone who will listen that Rudin has ignored the community’s need for a full service hospital, paid pennies on the dollar for this prime real estate, and now stands to sell luxury condos which will have a fair market value of more than a billion dollars.

She has big plans, she tells me, for the “second part of her life” that have to do with healing. But she’s keeping them secret for now.

Suzannah’s blog can be found at http://suzannahbtroy.blogspot.com/2011/11/howard-rubenstein-rudins-pr-dont-have.html

Silvia's Interview

with Christine Cody, Photographer

December 13, 2011

When I look at Christine Cody, I think “luminous.” Her skin, her eyes, her face, her manner: resplendent. When I look at her photography, I can’t take my eyes away.

Here I must borrow from the press release for Christine’s New York City solo show:

“The works of Christine Cody speak with an eloquent ambiguity. Her imagery tends to blend fashion with dark fantasy and a flare of 50’s elegance. Confrontational lyricism plays with the viewer – a dialogue that feeds off an interplay of values (literal and figurative). Her approach is like a storyteller, relating myths, secrets, and humor. Cody tends to confront her demons rather than evade them, often resulting in sultry, intimate visualizations. And it is this open course of phobias that we find both admirable and appealing.”

Christine was born and grew up in Los Angeles. She was raised Catholic but remembers having many questions in Catholic school: “why the apple? Why the flood?”; the answer she got – “just because” – disturbed and discouraged her but didn’t stop her probing. Finally she was asked to leave catechism class. She left the states to attend the Kunst Academy in Salzburg and later the University of Stirling in Scotland and received her BFA degree from the Arts Center College of Design in Pasadena which she calls “the best art school in the world.”

Her parents were divorced when she was twelve and she was shuttled around to a series of homes, one of which was with a family who let her have cocaine. Her father married three times during her adolescence, marriages that brought with them stepchildren and stepmothers who treated her with indifference. She was told she had to buy her own clothes and baby sit to make money. She has two biological siblings, a brother and a sister, who have never been emotionally available. Her mother, an alcoholic except for the final fifteen years of her life, died of stomach cancer in 1989; Christine cared for her until the end. Her father died in 2000.

She moved from Los Angeles to Portland where her life and her livelihood was photography. She modeled and says she knows how to get what she wants from a model because she’s been on both sides of the camera. She was finally enjoying the perfect life and things couldn’t have been better.

One night she went to a party in Portland and had three glasses of wine. She had driven to the party but wanted to play it safe so she decided to leave her car there and walk the short distance home, only three main streets. It was on Burnside that she was struck by a hit and run driver and knocked over the Burnside Bridge and onto the freeway where three trucks ran over her. They called her father in Los Angeles and she was put into a teaching hospital; they considered her dead. She spent eight months in a coma and a total of one year in the hospital. She remembers laying there in her bed, powerless, unable to do anything but listen to the drone of the breathing machine.

As the healing progressed and she became hopeful about regaining her health, she started thinking about a trip to New York City. In 1995 her cousin Quita, an editor at New York Magazine, sent her to the Robin Rice Gallery in Greenwich Village; the Gallery was so impressed by her portfolio they offered her a solo exhibit. She realized she had to live in New York City and made the move permanent twelve years ago.

She has done commercial work for the advertising firms of Wieden & Kennedy, Lowe, Factory Design, and Sterling/Stepping Design. Her clients include Verve Records, Nike, Eddie Bauer, Starbucks, and Bolle Sunglasses. In addition to having an exhibit of her work tour Japan, her photographs have been exhibited in Los Angeles at the G. Ray Hawkins Gallery and in Portland, Oregon, at the SK Josefsburg Studio. Her work has appeared in Communication Arts magazine and Soma. She continues to be represented by the Robin Rice Gallery and the stock photography agency Getty Images; her photographs have sold worldwide and have appeared on book covers, CD’s, and billboards. She considers Greg Gorman one of her early mentors. The world of photography like so much of the creative arts has evolved. Photographers are rarely hired these days because advertisers go right to stock. The most important thing she has learned is that making it in the art world is 90/10: 90 percent business and 10 percent creativity. She doesn’t believe in five year plans and chooses to live day to day.

Her father was a child actor in Mickey Rooney movies and had a role in David Copperfield and she grew up loving black and white movies and playing dress-up. Every photograph Christine takes is partnered to a narrative that she formulates. First she will find a location and then the fable begins to evolve. She gives her work provocative and lyrical titles like “haven’t died a winter yet”, “storm damage”, “shy apologies and polite regrets” and “it was almost you.” Most people in her photographs from her Portland days were chance encounters — a woman who worked in a vintage clothing shop, a young girl she managed to come across. When in New York, her gallery suggested that it was time she started using real models.

Years ago her father offered her thirty thousand dollars toward an apartment; she took only $15,000 and used it to work with graphic designer Jerry Ketel for a promo; she gives me a copy, a beautiful black and white collection of her work. She laments that the world has gone digital and remains firm in her decision to shoot only film. She has two cameras, a 4×5 which she proudly pulls out to show me, snug in its sleek black case, and a 2 ¼” Hasselblad. She loves to get her hands in the chemicals and does all her own printing. “When I hear the lens open and close or I begin to see the print emerge from the tray, that’s when I know who I am; that is when I am complete.” She has wanted to be a photographer since she was twelve years old.

Christine says “What I attempt in my work is an exploration of the numerous characters within myself. Through the vehicle of found people I seek a calmness which I myself lack at this point in time. My photography is a channeling of the pain and heartache that would otherwise be overwhelming for me. The most imperative point of my work is the ability to express complete unbridled passion without having to make any explanations for my emotional intensity.”

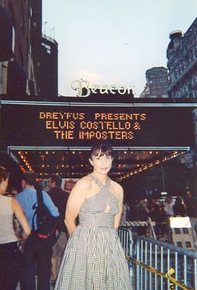

When I ask who has made the biggest impact on her life she has a list: “Eartha Kitt, Patsy Cline, Charlie Chaplin, Confucius, Gandhi, Fritz Lang, and Elvis Costello.” And who would you most like to meet? “If it is meant to be, the person I would most like to meet is my life partner.” What do you like best about yourself? “That I don’t feel sorry for myself.” Occasionally, she adds, she does get besieged during a particularly hard-hitting period and then she’s able to just say “f” it.

If you could be anywhere in the world right now, where would you be? “My own home.” Her greatest fear is homelessness, and her stress comes from worrying about what’s coming next – an anxiety visibly rooted in childhood as well as the reality of living in a city where landlords can be ruthless if they don’t want you there. Her favorite ways to spend time are cooking, cleaning, and working out, pursuits that are therapeutic and calm her. She is a Capricorn and a loner, dislikes liars and self-pitying people, but gets along well with others because she is careful with the quality of people she chooses as friends. If she was god, she would stop overpopulation and use energy to better the environment. Breakfast every morning is a smoothie blended from frozen berries, water, and soy protein.

For now she has no muse, no trigger, no one to inspire her, no one to rouse her to enthusiasm. Micheal, her boyfriend of a year and a half, died in September of this year. They met one day when she bought an air conditioner and was hauling it in a shopping cart down 14th Street; he followed her down the street, offered to help her get it home, and wouldn’t take no for an answer. Micheal was Polish, 32 years old, a foreman on a construction site. Christine says she always knew he had a strong artistic side because his apartment was colorful and intriguingly put together. They had a rocky relationship and had already broken up once because of his drinking. He would start the morning with a shot of vodka and tell her “A gentleman never drinks before two o’clock but I’m not always a gentleman.” One night he was acting strangely and she knew something was very wrong. She called 911 and when the paramedics got to the apartment, Micheal was out cold on the bed: “he’s just drunk; let him sleep it off.” She, however, was so highly agitated that they handcuffed her and took her to Bellevue Hospital. By the time she got back to the apartment, ten hours later, his condition had worsened. Every time she said she was going to call 911, he kept insisting no. She could see that things were rapidly getting worse and made the call. Four EMT responders came and worked on him in shifts for one hour. They finally declared him dead. “I try to live my life without regret,” she says, “but I wish I had done things differently. The first time I called 911 and they kept insisting he was just drunk I should have told them he had been having heart problems. And the second time I should have called much sooner no matter what he said. The technicians who came didn’t have paddles and maybe being in the hospital would have saved him.”

On her table is a beautiful photo of a sleeping Micheal and her cat, Boogala, who has been with her since she volunteered at the Jewish home 12 years ago. She smiles and says “they loved each other.”

Her buoyancy is astonishing; with the evils and ills of her childhood and the adversity she has suffered much of her life, she is an unstinting caregiver; she works as a nanny and devotes her time to taking care of others. She loves spending time with animals and has volunteered in animal causes. Her first volunteering experience was in a senior center in the tenderloin in San Francisco; then in a Jewish Home for the Aged in Los Angeles; and finally with Alzheimer’s patients in New York City “until Schlomo got a crush on me.”

Is there one thing you feel you absolutely must do every single day? “Express gratitude,” she tells me, “but I don’t manage to do it every day.”

Christine’s work can be found through a search for her name on Getty Images.com; under Past Exhibitions on the Robin Rice website at www.robinricegallery.com; and on her own website at www.christinecody50.com.

Here I must borrow from the press release for Christine’s New York City solo show:

“The works of Christine Cody speak with an eloquent ambiguity. Her imagery tends to blend fashion with dark fantasy and a flare of 50’s elegance. Confrontational lyricism plays with the viewer – a dialogue that feeds off an interplay of values (literal and figurative). Her approach is like a storyteller, relating myths, secrets, and humor. Cody tends to confront her demons rather than evade them, often resulting in sultry, intimate visualizations. And it is this open course of phobias that we find both admirable and appealing.”

Christine was born and grew up in Los Angeles. She was raised Catholic but remembers having many questions in Catholic school: “why the apple? Why the flood?”; the answer she got – “just because” – disturbed and discouraged her but didn’t stop her probing. Finally she was asked to leave catechism class. She left the states to attend the Kunst Academy in Salzburg and later the University of Stirling in Scotland and received her BFA degree from the Arts Center College of Design in Pasadena which she calls “the best art school in the world.”

Her parents were divorced when she was twelve and she was shuttled around to a series of homes, one of which was with a family who let her have cocaine. Her father married three times during her adolescence, marriages that brought with them stepchildren and stepmothers who treated her with indifference. She was told she had to buy her own clothes and baby sit to make money. She has two biological siblings, a brother and a sister, who have never been emotionally available. Her mother, an alcoholic except for the final fifteen years of her life, died of stomach cancer in 1989; Christine cared for her until the end. Her father died in 2000.

She moved from Los Angeles to Portland where her life and her livelihood was photography. She modeled and says she knows how to get what she wants from a model because she’s been on both sides of the camera. She was finally enjoying the perfect life and things couldn’t have been better.

One night she went to a party in Portland and had three glasses of wine. She had driven to the party but wanted to play it safe so she decided to leave her car there and walk the short distance home, only three main streets. It was on Burnside that she was struck by a hit and run driver and knocked over the Burnside Bridge and onto the freeway where three trucks ran over her. They called her father in Los Angeles and she was put into a teaching hospital; they considered her dead. She spent eight months in a coma and a total of one year in the hospital. She remembers laying there in her bed, powerless, unable to do anything but listen to the drone of the breathing machine.

As the healing progressed and she became hopeful about regaining her health, she started thinking about a trip to New York City. In 1995 her cousin Quita, an editor at New York Magazine, sent her to the Robin Rice Gallery in Greenwich Village; the Gallery was so impressed by her portfolio they offered her a solo exhibit. She realized she had to live in New York City and made the move permanent twelve years ago.

She has done commercial work for the advertising firms of Wieden & Kennedy, Lowe, Factory Design, and Sterling/Stepping Design. Her clients include Verve Records, Nike, Eddie Bauer, Starbucks, and Bolle Sunglasses. In addition to having an exhibit of her work tour Japan, her photographs have been exhibited in Los Angeles at the G. Ray Hawkins Gallery and in Portland, Oregon, at the SK Josefsburg Studio. Her work has appeared in Communication Arts magazine and Soma. She continues to be represented by the Robin Rice Gallery and the stock photography agency Getty Images; her photographs have sold worldwide and have appeared on book covers, CD’s, and billboards. She considers Greg Gorman one of her early mentors. The world of photography like so much of the creative arts has evolved. Photographers are rarely hired these days because advertisers go right to stock. The most important thing she has learned is that making it in the art world is 90/10: 90 percent business and 10 percent creativity. She doesn’t believe in five year plans and chooses to live day to day.

Her father was a child actor in Mickey Rooney movies and had a role in David Copperfield and she grew up loving black and white movies and playing dress-up. Every photograph Christine takes is partnered to a narrative that she formulates. First she will find a location and then the fable begins to evolve. She gives her work provocative and lyrical titles like “haven’t died a winter yet”, “storm damage”, “shy apologies and polite regrets” and “it was almost you.” Most people in her photographs from her Portland days were chance encounters — a woman who worked in a vintage clothing shop, a young girl she managed to come across. When in New York, her gallery suggested that it was time she started using real models.

Years ago her father offered her thirty thousand dollars toward an apartment; she took only $15,000 and used it to work with graphic designer Jerry Ketel for a promo; she gives me a copy, a beautiful black and white collection of her work. She laments that the world has gone digital and remains firm in her decision to shoot only film. She has two cameras, a 4×5 which she proudly pulls out to show me, snug in its sleek black case, and a 2 ¼” Hasselblad. She loves to get her hands in the chemicals and does all her own printing. “When I hear the lens open and close or I begin to see the print emerge from the tray, that’s when I know who I am; that is when I am complete.” She has wanted to be a photographer since she was twelve years old.

Christine says “What I attempt in my work is an exploration of the numerous characters within myself. Through the vehicle of found people I seek a calmness which I myself lack at this point in time. My photography is a channeling of the pain and heartache that would otherwise be overwhelming for me. The most imperative point of my work is the ability to express complete unbridled passion without having to make any explanations for my emotional intensity.”

When I ask who has made the biggest impact on her life she has a list: “Eartha Kitt, Patsy Cline, Charlie Chaplin, Confucius, Gandhi, Fritz Lang, and Elvis Costello.” And who would you most like to meet? “If it is meant to be, the person I would most like to meet is my life partner.” What do you like best about yourself? “That I don’t feel sorry for myself.” Occasionally, she adds, she does get besieged during a particularly hard-hitting period and then she’s able to just say “f” it.

If you could be anywhere in the world right now, where would you be? “My own home.” Her greatest fear is homelessness, and her stress comes from worrying about what’s coming next – an anxiety visibly rooted in childhood as well as the reality of living in a city where landlords can be ruthless if they don’t want you there. Her favorite ways to spend time are cooking, cleaning, and working out, pursuits that are therapeutic and calm her. She is a Capricorn and a loner, dislikes liars and self-pitying people, but gets along well with others because she is careful with the quality of people she chooses as friends. If she was god, she would stop overpopulation and use energy to better the environment. Breakfast every morning is a smoothie blended from frozen berries, water, and soy protein.

For now she has no muse, no trigger, no one to inspire her, no one to rouse her to enthusiasm. Micheal, her boyfriend of a year and a half, died in September of this year. They met one day when she bought an air conditioner and was hauling it in a shopping cart down 14th Street; he followed her down the street, offered to help her get it home, and wouldn’t take no for an answer. Micheal was Polish, 32 years old, a foreman on a construction site. Christine says she always knew he had a strong artistic side because his apartment was colorful and intriguingly put together. They had a rocky relationship and had already broken up once because of his drinking. He would start the morning with a shot of vodka and tell her “A gentleman never drinks before two o’clock but I’m not always a gentleman.” One night he was acting strangely and she knew something was very wrong. She called 911 and when the paramedics got to the apartment, Micheal was out cold on the bed: “he’s just drunk; let him sleep it off.” She, however, was so highly agitated that they handcuffed her and took her to Bellevue Hospital. By the time she got back to the apartment, ten hours later, his condition had worsened. Every time she said she was going to call 911, he kept insisting no. She could see that things were rapidly getting worse and made the call. Four EMT responders came and worked on him in shifts for one hour. They finally declared him dead. “I try to live my life without regret,” she says, “but I wish I had done things differently. The first time I called 911 and they kept insisting he was just drunk I should have told them he had been having heart problems. And the second time I should have called much sooner no matter what he said. The technicians who came didn’t have paddles and maybe being in the hospital would have saved him.”

On her table is a beautiful photo of a sleeping Micheal and her cat, Boogala, who has been with her since she volunteered at the Jewish home 12 years ago. She smiles and says “they loved each other.”

Her buoyancy is astonishing; with the evils and ills of her childhood and the adversity she has suffered much of her life, she is an unstinting caregiver; she works as a nanny and devotes her time to taking care of others. She loves spending time with animals and has volunteered in animal causes. Her first volunteering experience was in a senior center in the tenderloin in San Francisco; then in a Jewish Home for the Aged in Los Angeles; and finally with Alzheimer’s patients in New York City “until Schlomo got a crush on me.”

Is there one thing you feel you absolutely must do every single day? “Express gratitude,” she tells me, “but I don’t manage to do it every day.”

Christine’s work can be found through a search for her name on Getty Images.com; under Past Exhibitions on the Robin Rice website at www.robinricegallery.com; and on her own website at www.christinecody50.com.

Silvia's Interview

with Eze Bongo, Artist

December 22, 2011

Eze Bongo was born in Trials, Saint Anthony, Montserrat, on July 29, 1976. A Leo. Those born under this sign are considered by most modern astrologers as natural leaders. They are also considered as outgoing, proud, warm-hearted, loyal, and notable for their wish to excel in all they do. Leo personalities are known to love those they are close with and their wish to protect and defend all those that need it. Eze is all this and more. He is all artist.

When I first met Eze about eight years ago, I commented on his compelling jewelry. He flashed one of his magnetic smiles and told me he designed and fabricated it. The more I got to know him, the more I believed he had the power to master anything. He seems to have that dazzling instinct of looking at something and understanding how it’s done. He is a master carpenter, a woodcarver, a welder, a plumber, an electrician, a furniture designer, a painter, a musician, and a poet. Last spring he gave me an autographed copy of his beautiful book Fabiruckus, a collection of poems and narratives, a stirring look into growing up in Montserrat.

His mother was in labor with him for 24 hours and he has always had enormous respect for the struggle she endured to bring him into this world. They are great friends and she has always been more like a sister. He was raised by his great grandmother, who was the head of a plantation and 105 when she died. Growing up, he was taught to love, to respect, and to demand respect from others. He never experienced servitude. There was always plenty of food and whatever excess there was went to those in need. His grandfather would bring him fresh milk and bush tea, a tea made from herbs. He was breast fed until he was a year old and never had canned milk. When he was very young he had a severe panic attack which was treated by washing him with bark. His favorite pastime was making toys; as a young boy he made cars and in his early teens, tables and benches. He walked a half mile to school every day, looked forward to going, and his favorite subject was English. He was expected to be in the top five in his class and was always a straight A student. He was the first in his family to get a diploma and says he did it only for his family. He places no value on the academic methods of rewarding students with gold stars and ribbons – he says he is not a dog who does what his master wants in order to get a treat. Eze once read the encyclopedia straight through from A to Z and says all that raw information is still in his head. Knowledge, he tells me, is transmitted through the air we breathe. He continues to embrace learning.

He credits his favorite childhood memory to being lucky enough to grow up with his grandparents. Of all the things he learned from them, the most valuable was to be self sufficient. I asked if he has a five year plan, but he says no, he lives day to day because nothing is guaranteed. The blueprint he grew up with was not so much about rewards or retribution; it was about “doing what you can do.” His grandfather would work in the mountains all day long and Eze would say “why don’t you get a tractor?” His grandfather would shake his head and simply say “you don’t get it.” “I used to wonder why my grandfather never hired government tractors to plow his ground. Now I realize he was doing it for the fun of it all. Now I am working on my own house and people are asking me why I don’t hire people — truth is I am having the time of my life.”

Eze grew up with no curfews. All that he was required to do was to take care of his responsibilities. He had to get up every morning at five a.m., seven days a week. Even if he went to bed at four a.m. he still had to get up at five. Otherwise, he’d get cold water thrown on him. At the age of 13 Eze already had his “own ground,” a farm; Montserrat no longer challenged him and his mother encouraged him to leave. He arrived alone in New York Cityin 1993 and went to live with his uncle. His entire family, brothers and sisters, are still down there. He has never gone back.

The tradition in Montserrat is to name a baby after someone who has died. Even before the baby is conceived, the belief is that the mother or grandmother has a vision and knows how to name the baby when it comes. Eze has a daughter who is 15 and a son who is 12; his son is named after his grandfather and amazingly exhibits the same behaviors and displays the same conduct as his grandfather. And even though his son has never been to Montserrat, he speaks Creole English as though he had lived there all his life.

Eze is outspoken, out there, and upfront. How about: “Somebody should of told Kim Kardashian that once u go black u can’t go back. Reggie tap that ass like a black man should. White boy got played.” He knows what he wants. He lives life the way it feels right to him, but remains highly principled, living life well but with a conscience. He is a Rasta and Rastas are spiritual gurus. They are never subservient, never compliant, never subjugated to the values of society. They are liberated, never dominated. The more he talks about it, the more I understand it is a way of life that I deeply respect. He says things like “cast no shadow, blame nor doubt, make no excuses, regrets or apologies. Be unprecedented — back down from nothing or no one, stay committed to fundamentals.”

Is there one thing you absolutely must do every day? “Be creative. The toughest thing about being creative is finding the time to do it.” He sometimes finds it challenging to work with people on inspired projects because he has his own ideas; “people can break my rhythm.”

These days when he takes a break from the renovations he is working on both in upstate New York and in Brooklyn, he does a lot of his creating on Facebook. It is a unique medium and it is where he shares his soul. I commented on the close to 1500 Facebook friends he has and ask if he really knows them all personally; he tells me yes. Two-thirds of the island’s population was forced to flee after the eruption of the Soufriere Hills volcano in July of 1995; they migrated to all parts of the world . . . and they’re pretty much all on Facebook.

His Facebook posts are peppered with his plans for designing a couch, his witticisms, his shrewdness, his adventures in and out of the city, and the word pum pum. Judging from his Facebook status, he spends an enormous amount of time on porn sites which could be why he is always beaming. He tells me porn is what calms him down. “Some hot gal put some sexy pictures on the internet before they got old or die of whatever reasons and am thankful for their thoughtfulness. If they never did anything else in their life they sure place a smile on my face and a warmth in my heart.”

His words: “I don’t want to hear fuck all about your hard life; tell me more about your sex life if its more interesting and inspiring. The hard life is too depressing; a great sex life is worth an intriguing and entertaining listen.”

“I got this invincible, untouchable, indestructible feeling running trough my veins. Am running on full throttle plowing trough the waves of emotions life throws at me, my head does now bow it dives and split the waves with equal force. I am channeling and commanding an icebreaker heading to the north pole. I will go trough the iceberg or move it out the way.”

While his strength is sexual energy which he assures me he can transform into creative muscle, he is defenseless to people who get emotionally tangled up with him when he doesn’t feel the same about them – women who have fantasies, women who want to take care of him, and women who want to marry him. “Love is a security blanket for the insecure, sex is the installment payments. You can only be covered by one policy or person at a time.

Eze doesn’t drink and has never taken a drug in his life, never even smoked weed. He says he never needed it because he was never confined. No one has ever broken his spirit. He has never filled out a job application because he considers it degrading. He counsels: never let anyone take your euphoria from you.

Punk rock was the music most popular when he was growing up, especially the Ramones and some British bands, but his favorite was Bob Marley and the Wailers. He says Trinidad has the best music and that is where Jamaicans study; after all, he tells me, it was Trinidad that invented the steel pan. He started playing music when he was five years old; he made a guitar out of a piece of wood with nylon strings and taught himself how to play in his own back yard.

Most of the time he exists in what he calls the spirit realm and at times admits to going completely out of his mind. He claims a warrior spirit and says “what I do for excitement is not what normal people do.” Like what? I ask. “I put on African music and throw spears.” Where? “In my living room.”

He works 12 hour days seven days a week, seemingly with unlimited energy, yet always a perfectionist. ”If it’s not excellence it’s not good enough and you should be sorry cause it is sorry and a sad expectation of self worth, skill and abilities.” He has both the emotional drive and the physical capacity to overwork, but he trusts his body and says the body knows itself and you have to listen to it and let it shut down when you hear it begging for that. “Saving yourself and energy is like saving your Sunday best for when you’re dead and someone uses your best to go work ground. I’ve seen it done before and it prompted me to say fuck that — I want my best now!”

What kind of people do you dislike, I ask. He doesn’t dislike anybody, then pauses and says well, maybe he does dislike some people’s principles. “You are meant to have what you have” he explains and goes on with a story. His great grandmother couldn’t read or write and an aunt would regularly write her letters and enclose some money. The lady who took care of his great grandmother would be the first to pick up the mail and read the letters but would lie about the amount of cash enclosed and pocket a substantial part. The grandmother became aware of what was going on but let it go; she assured Eze that punishment would come to the woman when the time was right. “People lie to you because they fear you. If it comes to you, you take it. If it doesn’t come to you, you leave it.”

What would you do it you had a time machine? “I wouldn’t use it.”

What makes him angry? “When I give advice and people don’t take it. Then they ask me the same thing again and still don’t take it. They mess up and I have to clean up. I tell my son not to take his Ipod down the street but he does it anyway and then he loses it. People don’t think about what the outcome will be. They don’t know how to think for themselves.”

Tell me one thing about yourself you wouldn’t want me to know. “I’m afraid to perform in front of people I know.” He is very sensitive to the emotions of others and says that is something not a lot of people know about him that he wishes they would see. He admits to getting too caught up with how people perceive what he creates.

His big dream in life is to buy a boat and sail back toMontserrat.

How would you describe yourself in three words? “Arrogant, assertive, aggressive.”

What one thing that has happened in your life has made the biggest impact on who you are today? Lots of things, he tells me, many near death experiences: an almost fatal bicycle accident, getting washed away in a river, and most brutally, the Category 5 Hurricane Hugo in 1984. Debris was everywhere, people had to make sense out of how to eat, where to sleep; it was a total rebuilding effort. Did you lose a lot? I ask him. “No, I gained a lot.

“Some people think and feel the money they pay you is for you to barely survive on necessities and not for you to invest to be bigger and better than them. If me want food me go work ground; if I need water me go a river; if I need sleep I lay on the ground, if I want shelter I’ll sleep under a bridge. Get the point?”

What would you like to ask from God? “Nothing. God knows everything. I don’t have to ask him.”

On a scale of one to ten, how happy are you. Without skipping a beat, he says “10.”

For more Bongo and to order his book, visit his website at www.bongowarrior.com

When I first met Eze about eight years ago, I commented on his compelling jewelry. He flashed one of his magnetic smiles and told me he designed and fabricated it. The more I got to know him, the more I believed he had the power to master anything. He seems to have that dazzling instinct of looking at something and understanding how it’s done. He is a master carpenter, a woodcarver, a welder, a plumber, an electrician, a furniture designer, a painter, a musician, and a poet. Last spring he gave me an autographed copy of his beautiful book Fabiruckus, a collection of poems and narratives, a stirring look into growing up in Montserrat.

His mother was in labor with him for 24 hours and he has always had enormous respect for the struggle she endured to bring him into this world. They are great friends and she has always been more like a sister. He was raised by his great grandmother, who was the head of a plantation and 105 when she died. Growing up, he was taught to love, to respect, and to demand respect from others. He never experienced servitude. There was always plenty of food and whatever excess there was went to those in need. His grandfather would bring him fresh milk and bush tea, a tea made from herbs. He was breast fed until he was a year old and never had canned milk. When he was very young he had a severe panic attack which was treated by washing him with bark. His favorite pastime was making toys; as a young boy he made cars and in his early teens, tables and benches. He walked a half mile to school every day, looked forward to going, and his favorite subject was English. He was expected to be in the top five in his class and was always a straight A student. He was the first in his family to get a diploma and says he did it only for his family. He places no value on the academic methods of rewarding students with gold stars and ribbons – he says he is not a dog who does what his master wants in order to get a treat. Eze once read the encyclopedia straight through from A to Z and says all that raw information is still in his head. Knowledge, he tells me, is transmitted through the air we breathe. He continues to embrace learning.

He credits his favorite childhood memory to being lucky enough to grow up with his grandparents. Of all the things he learned from them, the most valuable was to be self sufficient. I asked if he has a five year plan, but he says no, he lives day to day because nothing is guaranteed. The blueprint he grew up with was not so much about rewards or retribution; it was about “doing what you can do.” His grandfather would work in the mountains all day long and Eze would say “why don’t you get a tractor?” His grandfather would shake his head and simply say “you don’t get it.” “I used to wonder why my grandfather never hired government tractors to plow his ground. Now I realize he was doing it for the fun of it all. Now I am working on my own house and people are asking me why I don’t hire people — truth is I am having the time of my life.”

Eze grew up with no curfews. All that he was required to do was to take care of his responsibilities. He had to get up every morning at five a.m., seven days a week. Even if he went to bed at four a.m. he still had to get up at five. Otherwise, he’d get cold water thrown on him. At the age of 13 Eze already had his “own ground,” a farm; Montserrat no longer challenged him and his mother encouraged him to leave. He arrived alone in New York Cityin 1993 and went to live with his uncle. His entire family, brothers and sisters, are still down there. He has never gone back.

The tradition in Montserrat is to name a baby after someone who has died. Even before the baby is conceived, the belief is that the mother or grandmother has a vision and knows how to name the baby when it comes. Eze has a daughter who is 15 and a son who is 12; his son is named after his grandfather and amazingly exhibits the same behaviors and displays the same conduct as his grandfather. And even though his son has never been to Montserrat, he speaks Creole English as though he had lived there all his life.

Eze is outspoken, out there, and upfront. How about: “Somebody should of told Kim Kardashian that once u go black u can’t go back. Reggie tap that ass like a black man should. White boy got played.” He knows what he wants. He lives life the way it feels right to him, but remains highly principled, living life well but with a conscience. He is a Rasta and Rastas are spiritual gurus. They are never subservient, never compliant, never subjugated to the values of society. They are liberated, never dominated. The more he talks about it, the more I understand it is a way of life that I deeply respect. He says things like “cast no shadow, blame nor doubt, make no excuses, regrets or apologies. Be unprecedented — back down from nothing or no one, stay committed to fundamentals.”

Is there one thing you absolutely must do every day? “Be creative. The toughest thing about being creative is finding the time to do it.” He sometimes finds it challenging to work with people on inspired projects because he has his own ideas; “people can break my rhythm.”

These days when he takes a break from the renovations he is working on both in upstate New York and in Brooklyn, he does a lot of his creating on Facebook. It is a unique medium and it is where he shares his soul. I commented on the close to 1500 Facebook friends he has and ask if he really knows them all personally; he tells me yes. Two-thirds of the island’s population was forced to flee after the eruption of the Soufriere Hills volcano in July of 1995; they migrated to all parts of the world . . . and they’re pretty much all on Facebook.

His Facebook posts are peppered with his plans for designing a couch, his witticisms, his shrewdness, his adventures in and out of the city, and the word pum pum. Judging from his Facebook status, he spends an enormous amount of time on porn sites which could be why he is always beaming. He tells me porn is what calms him down. “Some hot gal put some sexy pictures on the internet before they got old or die of whatever reasons and am thankful for their thoughtfulness. If they never did anything else in their life they sure place a smile on my face and a warmth in my heart.”

His words: “I don’t want to hear fuck all about your hard life; tell me more about your sex life if its more interesting and inspiring. The hard life is too depressing; a great sex life is worth an intriguing and entertaining listen.”

“I got this invincible, untouchable, indestructible feeling running trough my veins. Am running on full throttle plowing trough the waves of emotions life throws at me, my head does now bow it dives and split the waves with equal force. I am channeling and commanding an icebreaker heading to the north pole. I will go trough the iceberg or move it out the way.”

While his strength is sexual energy which he assures me he can transform into creative muscle, he is defenseless to people who get emotionally tangled up with him when he doesn’t feel the same about them – women who have fantasies, women who want to take care of him, and women who want to marry him. “Love is a security blanket for the insecure, sex is the installment payments. You can only be covered by one policy or person at a time.

Eze doesn’t drink and has never taken a drug in his life, never even smoked weed. He says he never needed it because he was never confined. No one has ever broken his spirit. He has never filled out a job application because he considers it degrading. He counsels: never let anyone take your euphoria from you.

Punk rock was the music most popular when he was growing up, especially the Ramones and some British bands, but his favorite was Bob Marley and the Wailers. He says Trinidad has the best music and that is where Jamaicans study; after all, he tells me, it was Trinidad that invented the steel pan. He started playing music when he was five years old; he made a guitar out of a piece of wood with nylon strings and taught himself how to play in his own back yard.

Most of the time he exists in what he calls the spirit realm and at times admits to going completely out of his mind. He claims a warrior spirit and says “what I do for excitement is not what normal people do.” Like what? I ask. “I put on African music and throw spears.” Where? “In my living room.”

He works 12 hour days seven days a week, seemingly with unlimited energy, yet always a perfectionist. ”If it’s not excellence it’s not good enough and you should be sorry cause it is sorry and a sad expectation of self worth, skill and abilities.” He has both the emotional drive and the physical capacity to overwork, but he trusts his body and says the body knows itself and you have to listen to it and let it shut down when you hear it begging for that. “Saving yourself and energy is like saving your Sunday best for when you’re dead and someone uses your best to go work ground. I’ve seen it done before and it prompted me to say fuck that — I want my best now!”

What kind of people do you dislike, I ask. He doesn’t dislike anybody, then pauses and says well, maybe he does dislike some people’s principles. “You are meant to have what you have” he explains and goes on with a story. His great grandmother couldn’t read or write and an aunt would regularly write her letters and enclose some money. The lady who took care of his great grandmother would be the first to pick up the mail and read the letters but would lie about the amount of cash enclosed and pocket a substantial part. The grandmother became aware of what was going on but let it go; she assured Eze that punishment would come to the woman when the time was right. “People lie to you because they fear you. If it comes to you, you take it. If it doesn’t come to you, you leave it.”

What would you do it you had a time machine? “I wouldn’t use it.”

What makes him angry? “When I give advice and people don’t take it. Then they ask me the same thing again and still don’t take it. They mess up and I have to clean up. I tell my son not to take his Ipod down the street but he does it anyway and then he loses it. People don’t think about what the outcome will be. They don’t know how to think for themselves.”

Tell me one thing about yourself you wouldn’t want me to know. “I’m afraid to perform in front of people I know.” He is very sensitive to the emotions of others and says that is something not a lot of people know about him that he wishes they would see. He admits to getting too caught up with how people perceive what he creates.

His big dream in life is to buy a boat and sail back toMontserrat.

How would you describe yourself in three words? “Arrogant, assertive, aggressive.”

What one thing that has happened in your life has made the biggest impact on who you are today? Lots of things, he tells me, many near death experiences: an almost fatal bicycle accident, getting washed away in a river, and most brutally, the Category 5 Hurricane Hugo in 1984. Debris was everywhere, people had to make sense out of how to eat, where to sleep; it was a total rebuilding effort. Did you lose a lot? I ask him. “No, I gained a lot.

“Some people think and feel the money they pay you is for you to barely survive on necessities and not for you to invest to be bigger and better than them. If me want food me go work ground; if I need water me go a river; if I need sleep I lay on the ground, if I want shelter I’ll sleep under a bridge. Get the point?”

What would you like to ask from God? “Nothing. God knows everything. I don’t have to ask him.”

On a scale of one to ten, how happy are you. Without skipping a beat, he says “10.”

For more Bongo and to order his book, visit his website at www.bongowarrior.com

Silvia's Interview

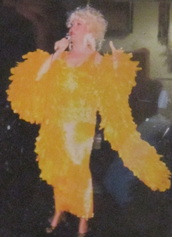

with Tish, Female Impersonator

February 10, 2012

Anyone who’s been around the Village for a while knows Tish. Colorful, compelling, and always a good neighbor, he can be found on sunny days on his Bank Street stoop presiding over his famous sidewalk sales, accompanied by the music of the forties coming from his radio. Tish will be 88 years old on February 24, 2012. He was the first person I met when I moved into my apartment on Bank Street. He would tease me about my boyfriends and I would tease him about his.

He was born Joseph Touchette and grew up in New England to French Canadian parents, an only child for almost seven years, spoiled by both sides of the family. He was the “petit garcon” which got garbled into half French and half English and became his nickname, Ti-boy. He is blessed with a large and close knit family: brother Dede, six years younger than Tish, and married 56 years; Bang, two years younger than Dede, and married 52 years; his brother Donnie who he used to take care of and who loved to hide in the maze of cornfields, now 57; his sister Agnes who lives in Florida; and his sister Rita who lives in Connecticut in his mother’s house. Tish lost one brother, Buck, who was born when Tish was 11 years old. When he goes home to his many nieces and nephews, he’s “Uncle Joe.”

Tish started working as a young boy. He recalls running across the field from school, dressed in a suit and tie, to work at the woolen mills factory. The mill was converted by the Germans and become known as William Primms Metals; they manufactured safety pins and bobby pins. Tish’s job was to thread the wire; he started out as the #3 boy who oiled the machines. Eventually he moved up to the #2 and then to the #1 boy where he supervised others. He weighed 98 pounds and was expected to lift 98 lbs. He laughs now and says “I didn’t know I was so macho.” He also worked at the La Rosa Macaroni Company.

He made $18 a week, gave his mother $12, and spent the remaining few dollars for tap dancing and ballet lessons at the Rhode Island Conservatory.

Tish sang in church at weddings, funerals, Sunday services and Tuesday night devotions to the Blessed Mother until he was 25. His closest friends were his piano teacher and her sister, the organist, two unmarried women known in those days as “old maids”. He had some friends who were likely gay but no one used that expression back then; anyone effeminate was called sissy or pansy. It was unsettling to be a gay person in so small a community, always wondering if you are the only one.

Early on Tish went to Boston and was so naïve he didn’t realize the dancing girls were all dancing boys. What he did realize was that he was in awe of the elegance of the experience. He was about 17 or 18 when he heard of a club in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, called a “gay bar.” The first time he saw two men dancing was at The College Inn in Boston and it took him a week to get over it. His uncle was in a jitterbug contest and one of the men dancing was a friend of his mother’s.

Tish was twenty, ready and eager to move to New York City, when his father died at the age of forty. This was the saddest time of his life not only because he loved and missed his father but because he knew it was up to him to stay home and help his mother who was then thirty eight years old. For the next six years he helped care for his siblings until his mother remarried a man who was a very good stepfather to Tish and the father of his brother Donnie. Tish lived across the street from the church where his grandparents were sextons and the cemetery was literally in his back yard. When his father died the family went directly from the house to the church to the cemetery and instead of taking a limousine they simply walked back to the house. Tish joked with his brother that all they had to do was look out their window to see if the wind blew the flowers off their father’s grave. His favorite subject in school was history and he loved walking through the graveyards of the different churches where he could see the tombstones of the French Canadians. The Protestant cemeteries were where the revolutionary war Yankees were buried.

One of his early jobs was at the legendary Celebrity Club in Providence, Rhode Island, believed to be the first interracial nightclub in New England, where he and his friend Bing would go for Sunday afternoon jam sessions. The club featured top national jazz and R&B acts as well as local talent in the 1950s. Musicians like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holliday would come to Providence and stay for week-long engagements. On one of those Sunday afternoons Louis Armstrong was there; he didn’t have all the members of his band with him, just six people. Tish heard the gravelly voice behind him “Wanna do a set?” And so Tish did “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “All of Me” with Louis and rounded out the afternoon at the bar talking with Armstrong’s singer, Thelma Middleton.

Tish had been working at the Wonder Bar in Norwich, Connecticut for six weeks when the owner received a letter from the State Liquor Authority (SLA) stating Tish could no longer work there in women’s attire because it was against the laws of the state of Connecticut for a man to wear female clothes. The Connecticut mill towns were struggling to deal with the SLA. So Tish’s career as a female impersonator – the word “drag” was never used – was delayed a while longer. He compares his appearance at that time to Adam Lambert: he didn’t want to break any laws but delighted in being obvious; he wore pants but lots of theatrical make-up. He had his brown hair curled and used his mother’s bleach to gradually lighten it. Three quarters of the audience was from the submarine base. Tish’s brother, then a sailor stationed in New London, would tell Tish how his friends would say what a great time they had at the club. Tish warned him not to let on that the star of the show was his brother – 80% might like it but the other 20% might want to kill him. He was so popular that the Wonder Bar put his picture in the Norwich Bulletin advertising “Miss Tish”. His friends, his family, his relatives, in fact the whole state accepted him as the “Joe” they always knew.

He left the Wonder Bar for the Stage Coach Inn in Voluntown, in the town of Norwich, the birthplace of Benedict Arnold, a club that had been a real stage coach inn during the Revolutionary War. It was across the street from a Catholic church. One afternoon a priest came in to the club. “Are you Tish?” the priest asked. “I have nothing against your show but when my parishioners come to seven o’clock confessions on Saturday evening, there’s no parking!” Tish’s fans from The Wonder Bar had followed Tish the twelve miles to the Stagecoach Inn. He assured the priest he would be there for only two more weeks because The Wonder Bar wanted him back. The owner there said that since Tish started, he had paid off his mortgage and gotten a new car.

Part of his act was telling the audience that the owner of the bar had decided that Tish should have other impersonators in his act and so he was going to audition some people from the audience. Tish would seriously scrutinize the room, pick out the three roughest looking sailors and prompt them to do exactly as he did; he would sashay around the room in flowing chiffon and, to the delight of the audience, the sailors would have to do exactly the same.

Tish met his first boyfriend when he was 27. Philip was 24, lived across from Brown University, and was planning to get married, when he visited a club in Pawtucket, Rhode Island where Tish was singing Sunday and Monday nights. The club was located next to Slaters Textile Mills, the first textile mill in the country, constructed in 1789. Tish tells the story of the seven clowns from Barnum & Bailey Circus coming to the club one night from the circus in Providence. The next day the circus moved on to Hartford where 67 people died in a huge fire, making that the last time Barnum & Bailey Circus was held under a tent.

Philip’s father was a sergeant in the Korean War and Philip introduced him to Tish in Connecticut. It was a congenial enough meeting but afterward his father made it clear to Philip that if he kept seeing Tish he’d have to move out. Philip lived in his car for three or four days without saying anything. Soon after he moved into the barn with Tish. The barn belonged to Tish’s great aunt and her husband who lived in a colonial home on the property. They had converted part of the barn to a two room apartment and when the couple would argue, that’s where the husband would sleep. Tish had been living with his mother but when she remarried and the apartment became available, Tish moved in and gave his aunt three dollars a week. There was no plumbing and no water and he cooked with a kerosene stove and used an outhouse at the bottom of the hill, but he loved living there and stayed for two years.